Why we named our rules engine Sherlock

Building an if-this-then-that framework for workflow automation. The internal debates, the disagreements on scope, and why testing rules before deployment became the defining feature.

Rules-based automation is the heart of intelligent workflow management. Here is how we approach it.

Workflow Automation Software Made Easy & Simple

Summary

If-then workflow rules - this is our personal, candid experience building them at Tallyfy. Not a polished case study. The actual debates, sketches, and moments of doubt.

- The vision was bigger than validation - We wanted rules that could trigger actions across entire workflows, not just validate form fields. This sparked a scope debate that shaped everything.

- Test before deploy - The phrase “try an input, see the result Sherlock would give you” became our design north star for the testing interface.

- Rules fire once by design - A decision that seems obvious now but required explicit engineering. Once triggered, a rule cannot be triggered again on the same process.

- The overthinking question - I genuinely wondered if we were over-engineering this. The honest answer? We probably were. And it was worth it.

There is way more behind this than I can share publicly. The architecture decisions, the edge cases, the customer requests that forced us to rethink assumptions - most of that stays internal. But the origin story and the debates that shaped the direction? Those are worth telling. This reflects our experience at a specific point in time. Some details may have evolved since, and we have omitted certain private aspects that made the story equally interesting.

If you want to see where this ended up, check the automations documentation or the if-this-then-that tutorial. What follows is how we got there.

April 26, 2018

I posted this to our internal product design board, trying to articulate something I had been thinking about for months:

“It seems like people need an extensible framework that not only validates form fields, but also lets them write custom rules which trigger the this within if this then that.”

That sentence took me twenty minutes to write. The concept was clear in my head but getting the words right mattered. We were not building a simple validator. We were building a rules engine that could power conditional logic across an entire workflow system.

I named it Sherlock. More on that in a moment.

The MVP conditions we sketched out

I drew four whiteboards that day. The first sketched out what rules would actually do:

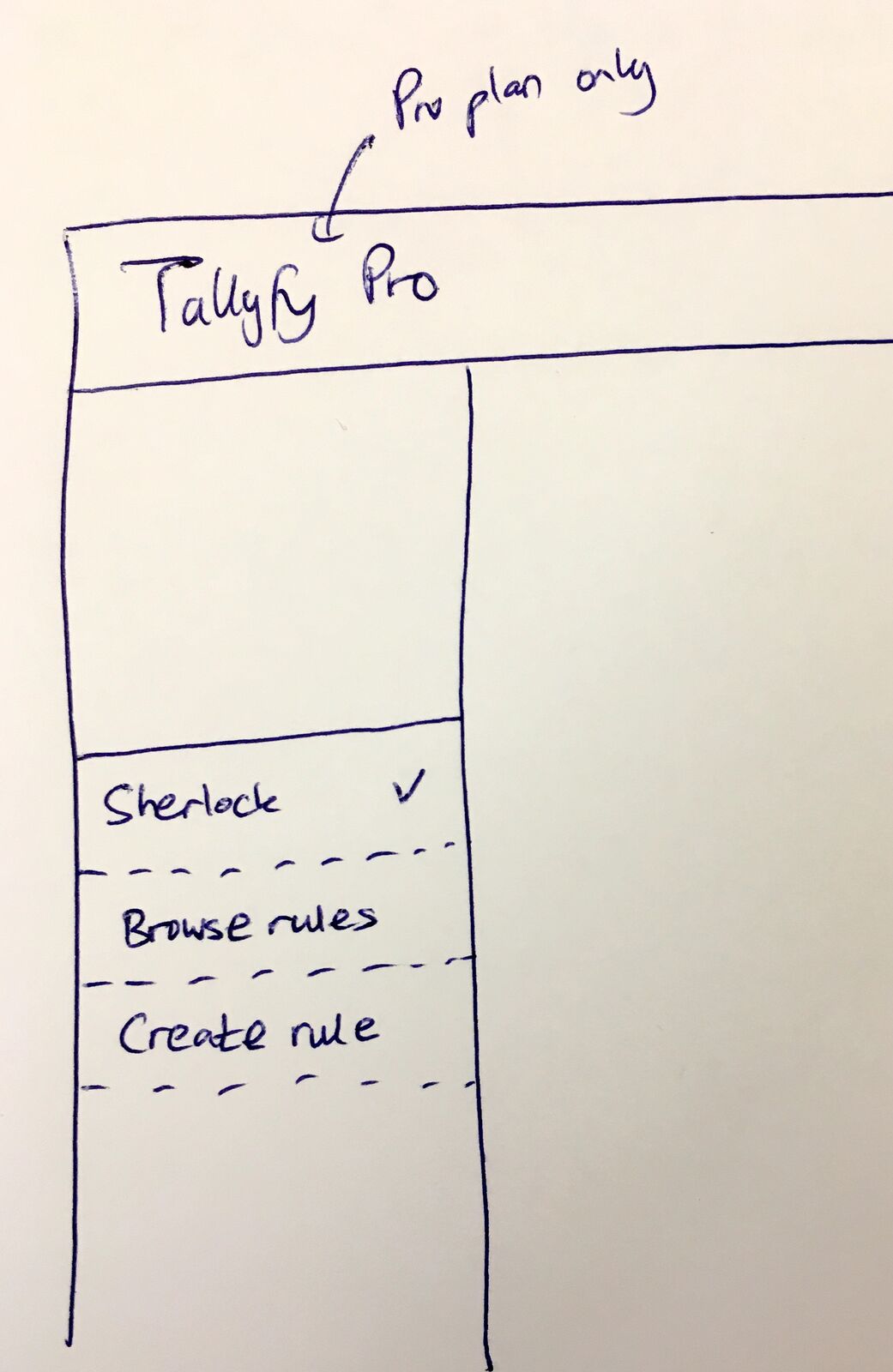

The original sketch: Sherlock as a sidebar feature, Pro plans only. April 26, 2018.

The original sketch: Sherlock as a sidebar feature, Pro plans only. April 26, 2018.

The simplest use cases I could articulate:

- If (form-text-box) value is (a number) AND “>4500” then hide this step.

- If (form-text-box) value is “Nashville” then re-assign task (select another task) to (set of people)

These two examples captured what we were after. Rules that check values. Rules that trigger actions. Not just “is this field valid?” but “based on this field, what should happen next?”

I wrote in the original post:

“It could sit on the left sidebar for pro plans only.”

That placement decision - Pro plans only, left sidebar - was not arbitrary. We knew this feature would be complex to build and complex to use. Limiting it to Pro plans bought us time to get it right before wider exposure.

Creating a rule

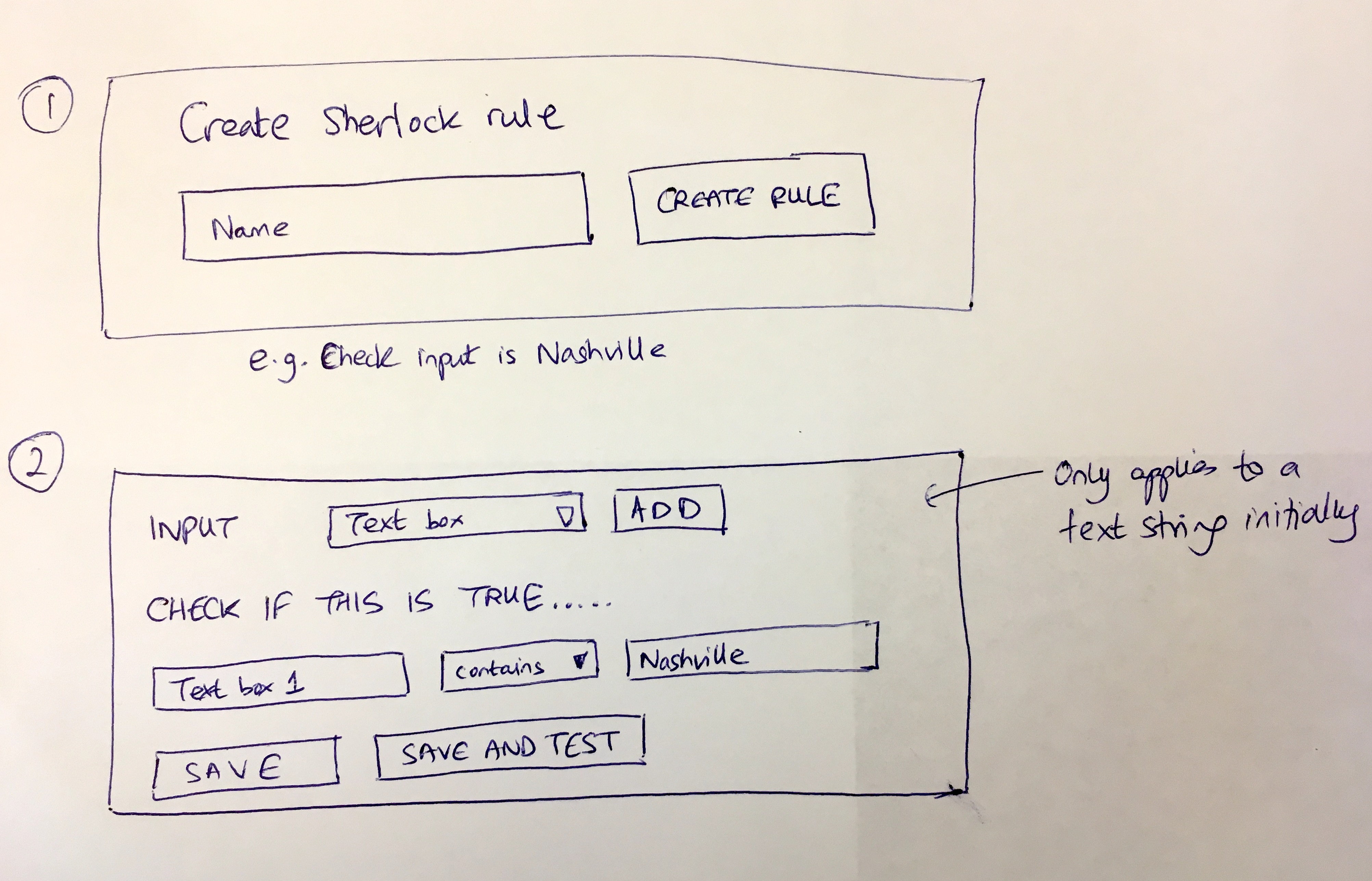

Sketching the rule creation UI. The Nashville example became our reference case throughout development.

Sketching the rule creation UI. The Nashville example became our reference case throughout development.

“Creating a rule could use the same UI as creating a template, it needs a name, then you build a rule.”

The sketch shows what we were thinking:

- Step 1: “Create Sherlock rule” - give it a name (e.g., “Check input is Nashville”)

- Step 2: Build the condition - INPUT type (text box), CHECK IF THIS IS TRUE (Text box 1 contains “Nashville”), then SAVE AND TEST

That last button - “SAVE AND TEST” - became everything.

Where the name came from

“After you build a rule, you need to test it. i.e. try an input … see the result Sherlock would give you …”

That is the exact sentence where Sherlock got its name. Sherlock the detective examines evidence and reaches conclusions. Our Sherlock would do the same: give it inputs, watch it deduce the result.

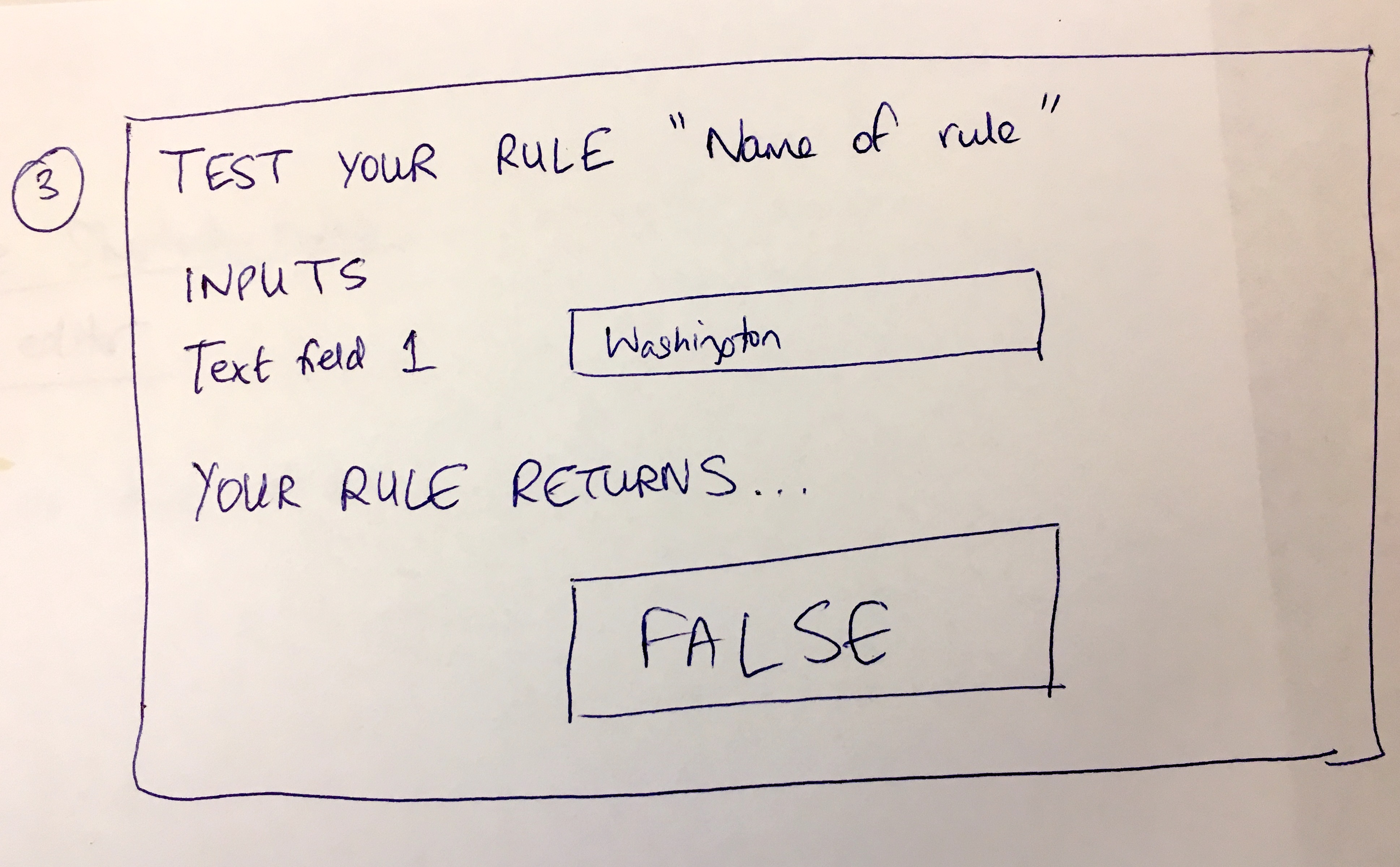

The testing interface concept. Enter “Washington” when the rule expects “Nashville” - Sherlock returns FALSE.

The testing interface concept. Enter “Washington” when the rule expects “Nashville” - Sherlock returns FALSE.

The sketch shows the testing flow:

- TEST YOUR RULE “Name of rule”

- INPUTS: Text field 1 = “Washington”

- YOUR RULE RETURNS… FALSE

Simple. Direct. Before deploying any rule to production, you could experiment. See what happens with different inputs. Catch mistakes before they affect real work.

Making rules reusable

The fourth sketch addressed the bigger vision:

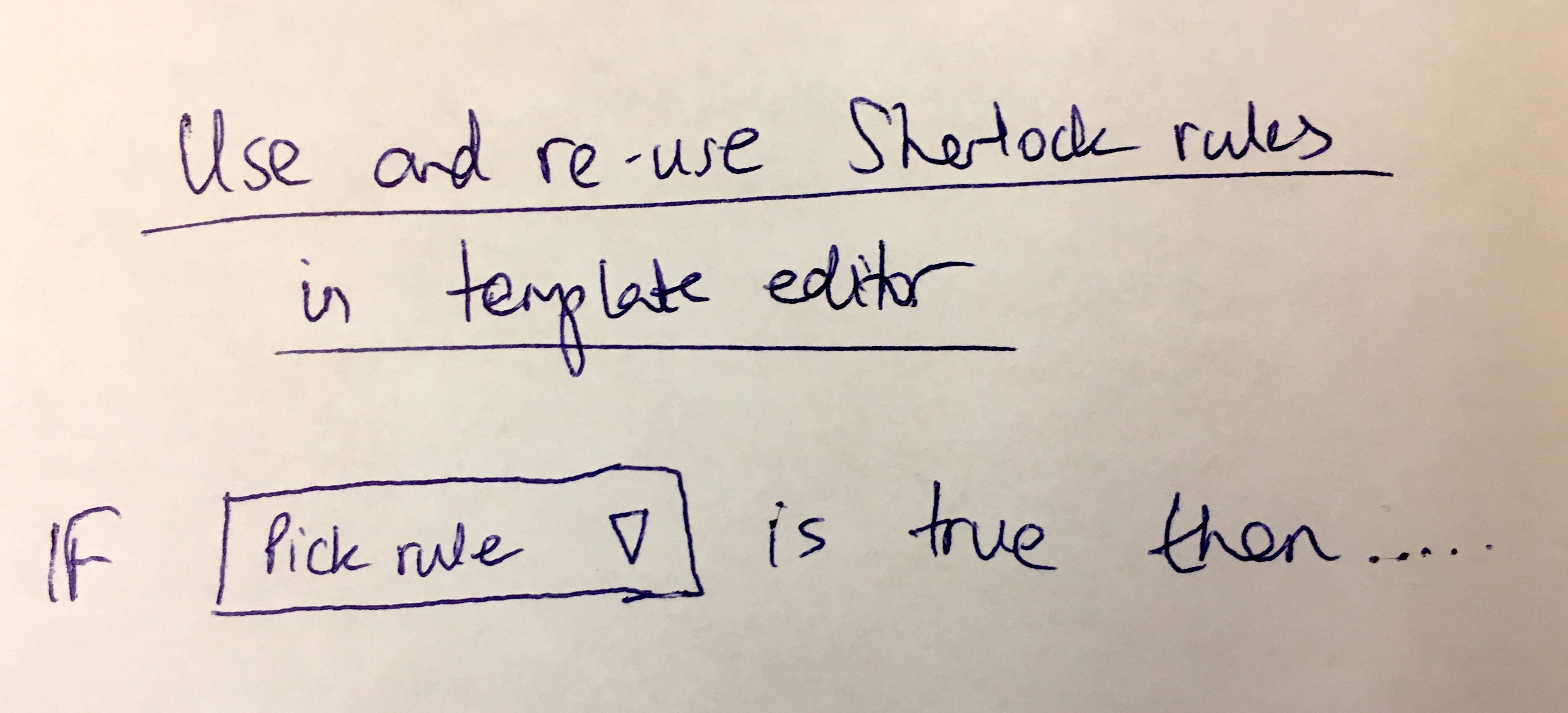

The reusability concept: “IF [Pick rule] is true then…”

The reusability concept: “IF [Pick rule] is true then…”

“Finally, in the template editor - you could just re-use the pre-built Sherlock rule in a form field or in an ‘if this then that’ rule.”

This was the ambitious part. Build a rule once. Use it everywhere. In form validation. In conditionals. Across templates. A library of logic that any workflow could reference.

The disagreement that shaped our scope

Five days later, on May 1st, Pravina pushed back hard:

“As discussed yesterday, this should be focused on form field validation (not conditions/rules) to start with.”

She was not wrong. My vision was sprawling. She wanted focus.

She laid out a specific user story:

“User wants to ensure that the value entered in a form field has 10 digits for a US phone number.”

Her acceptance criteria were precise:

- Developers will be able to develop this custom form field validation

- Developer then submits it to Tallyfy for approval

- Tallyfy ensures that it is: 1. QA’ed, 2. has a sensible name, 3. description, 4. alert when not matched (false) etc. (Example: US phone number - 10 digits required)

- Tallyfy publishes it

- It now appears as a form field type in the form field type list in Step > Forms tab (in PRO plans only)

- Users on PRO plan can then see and select “US phone number”

Her version was achievable. Scoped. Buildable.

What convinced us to start with validation was the feedback from pharmaceutical companies evaluating our platform. They needed to ensure form fields matched specific formats - lot numbers, batch IDs, regulatory identifiers - before allowing the workflow to proceed. One pharma company had over 100 different data validation requirements across their vendor assessment questionnaires. Starting with validation gave us real patterns to learn from before tackling the harder conditional logic problem.

I agreed, mostly:

“Agreed. Form field rules could be separated out and then become re-usable within any form field on any template. I will try to work on a UI impression for this.”

The tension between “validation-first” and “full conditional logic” defined our roadmap for years. She was right to narrow the scope initially. I was right that we would eventually need the bigger vision.

The error message problem

One design challenge surfaced early in the original post:

“When Sherlock rules are built - non-validation must result in a reason e.g. the number you entered is not >5000. Hence, the Sherlock rule builder must force reasons for non-validation states.”

Rules that fail silently are useless. If a user enters “Washington” when you expected “Nashville”, the system cannot just say “wrong” - it has to explain why.

This meant the rule builder itself had to require error explanations:

“It might be that you have to build a validation-ok state and all validation-bad states separately.”

Not just “what happens when the rule passes” but “what message appears when the rule fails.” Every rule needed both paths designed explicitly. This doubled the complexity of rule creation. It was worth it.

The overthinking question

I wrote this in my original post:

“Maybe I’m overthinking Sherlock as a separate service for re-usable rules, since the MVP could simply be to add a bunch more ‘this’ possibilities within ‘if this then that’.”

Honest self-doubt. Was I over-engineering?

The alternative was simpler: instead of building a whole rules framework, just add more condition options to our existing if-this-then-that feature. String matching. Number comparisons. Basic operators.

I had found an example from another product showing exactly this pattern - simple string matching options like “contains”, “does not contain”, “equals”, “does not equal”. Maybe that was enough.

It was not enough. But asking the question out loud kept us grounded.

Rule types: the architecture evolution

Later in development, we hit a design crossroads. The original implementation only had one rule type - show/hide rules for conditional visibility. But the architecture needed to be extensible.

From an internal discussion:

“Today - we have one type of rule - a show/hide rule. Without changing the fundamentals of rules, please add a ‘type’ property to a rule.”

This seems obvious in retrospect. Of course rules need types. But at the time, adding a type property meant rethinking how rules were stored, evaluated, and applied. Show/hide was just the beginning. Assignment rules, deadline rules, notification rules - they all needed the same underlying framework with different actions.

The type property became the foundation for everything that followed.

Rules fire once - intentionally

One behavior that confused users initially was intentional by design:

“FYI - all rules only fire once, once triggered, they cannot be triggered again.”

This was not a bug. It was a deliberate architectural decision.

Consider the alternative: a rule that fires every time its condition is evaluated. Change a form field? Rule fires. Change it back? Rule fires again. Change it again? Rule fires a third time. Users would be constantly surprised by cascading effects they did not anticipate.

Rules fire once. When the condition first becomes true, the action executes. After that, the rule is spent for that process instance. Predictable. Debuggable. Sane.

We learned this lesson the hard way. In our conversations with financial services teams, a common requirement was conditional approval routing - if a purchase request exceeds a certain threshold, route to a senior approver. One bank we worked with had approval thresholds at $500K and $1M that triggered different approval chains. If rules could re-fire every time someone edited a form field, users would be constantly surprised by cascading assignment changes. The “fire once” principle emerged directly from these enterprise requirements.

There are edge cases where users want rules to re-fire. We handle those differently. But the default behavior of “fire once” solved more problems than it created.

Templates that use conditional approval routing

The future we sketched

I wrote about where Sherlock could go:

“Within rules, you can write custom Javascript code which runs whatever you like. In future, Sherlock could be an independent rules-as-a-service which is aimed at developers to validate any data as a scalable client-side service. A Sherlock Library can be provided or pre-built rules to ease usage.”

Rules-as-a-service. A Sherlock Library. Custom JavaScript execution.

Some of this we built. Some remains on whiteboards. The original vision was deliberately larger than what we could ship immediately - it gave us a direction even when we had to narrow scope.

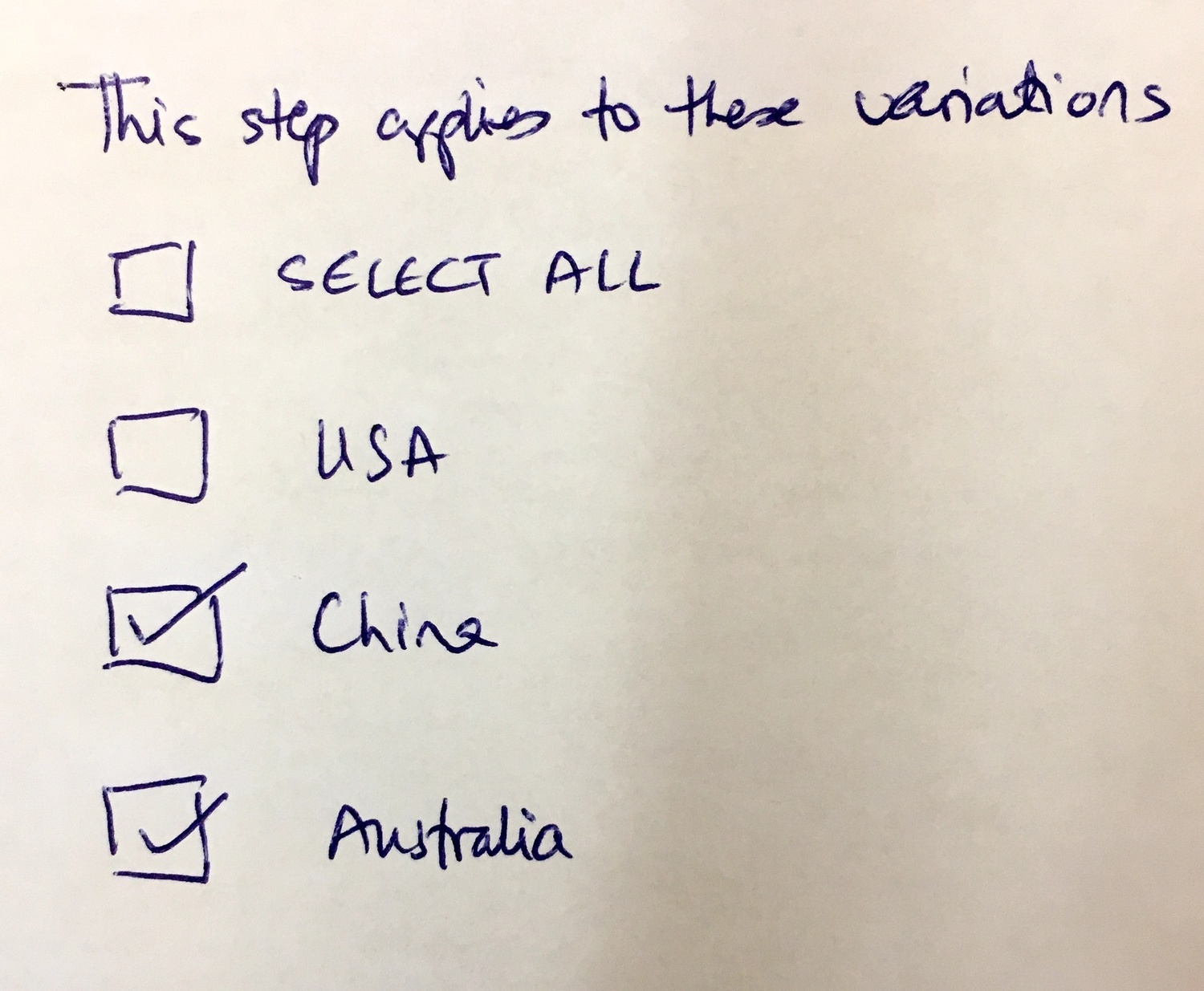

Regional variations

A day later, we were sketching related concepts:

“This step applies to these variations” - USA, China, Australia. Rules that toggle workflow sections by region.

“This step applies to these variations” - USA, China, Australia. Rules that toggle workflow sections by region.

This sketch shows how rules connect to broader workflow architecture. If you ship to China, certain steps appear. If you ship to Australia, different steps. Same template, conditional sections based on input.

The Sherlock rules engine had to power this. A rule that checks a region field. A workflow that shows or hides entire sections based on that rule’s result.

This is what workflow design actually looks like. Not just forms and tasks. Conditional paths. Regional variations. Rules that cascade across interconnected systems.

What we left out

There are architecture decisions behind Sherlock that remain internal. How rules execute in sequence. How we prevent infinite loops when rules reference each other. How the testing sandbox isolates rule evaluation from live data. The caching strategies. The evaluation order when multiple rules could fire simultaneously.

These details matter enormously for implementation. They are not essential for understanding the design philosophy. And some things should stay inside the building.

Four months later

On August 18, 2018, I linked the Sherlock discussion to a related planning task:

“Sherlock Apps - first starting with form field validation apps - UI needed, then proceeding to be…”

The scope conversation had resolved. Start with validation. Build toward the full conditional vision. One step at a time.

Where it stands now

Years later, the rules engine handles conditional visibility, dynamic assignment, calculated deadlines, and approval routing. The whiteboard sketches from April 2018 became production features used across thousands of workflows.

The automations documentation shows what we shipped. The if-this-then-that tutorial walks through how users actually build these rules today. The UI is cleaner. The capabilities are broader. The core concept - test before deploy, explain failures clearly, fire once - survived intact.

The name stuck. Try an input, see the result Sherlock would give you.

About the Author

Amit is the CEO of Tallyfy. He is a workflow expert and specializes in process automation and the next generation of business process management in the post-flowchart age. He has decades of consulting experience in task and workflow automation, continuous improvement (all the flavors) and AI-driven workflows for small and large companies. Amit did a Computer Science degree at the University of Bath and moved from the UK to St. Louis, MO in 2014. He loves watching American robins and their nesting behaviors!

Follow Amit on his website, LinkedIn, Facebook, Reddit, X (Twitter) or YouTube.

Automate your workflows with Tallyfy

Stop chasing status updates. Track and automate your processes in one place.