Why one process should not mean fifteen duplicate templates

When your shipping process differs slightly by country, most teams clone their template fifteen times. This creates a maintenance nightmare. We designed a better approach: define variations from Standard and visualize the difference between one variation and another.

Template variations prevent the maintenance nightmare of duplicate SOPs. Here is how we approach SOP management.

SOP Management Made Easy

Summary

Workflow template variations - this is our personal, candid experience designing them at Tallyfy. Not theory. The 15-template problem, the regional variation use case, and why we built variations instead of just cloning.

- Template duplication creates maintenance hell - Instead of just duplicating templates and having say 15 copies of the same template (each only slightly different), people should build a master process and define all the little variations

- Step-level variation tagging is the answer - When designing a step, you can tick which variations this step applies to: USA, China, Australia, or select all

- The rule complexity problem is real - The problem occurs when a rule is tied to another step which either is or is not in the current variation

- Process variation management is a key strength lacking in traditional approaches like Visio and most workflow tools. See how Tallyfy handles conditional logic

This reflects our experience at a specific point in time. Some details may have evolved since, and we have omitted certain private aspects that made the story equally interesting.

Here is something that has been bothering me for years.

Say you ship t-shirts and have an order fulfillment process. You ship to 8 countries. Your process is 90% the same, but it changes slightly country-by-country. Shipping to China has an extra customs step that shipping to the US does not.

What do most teams do? They clone their template. Eight times. For eight countries.

Now you have eight templates to maintain. Change the pricing step? Update all eight. Add a quality check? Update all eight. Forget one? Congratulations, your China team is now shipping with outdated procedures.

The 15-template problem

This is not a hypothetical scenario. In our templates, you might have steps that are slightly different per-country or per-type-of-customer.

In discussions we have had with enterprise operations teams, this pattern emerges constantly. A financial services firm with staff productivity variations of four to ten times between their least and most effective employees told us their biggest challenge was not the processes themselves - it was maintaining consistency across regional variations while still allowing for local requirements. They had the same fundamental workflow running in different jurisdictions, each with slightly different compliance steps.

Back in April 2018, I articulated the core problem in an internal design discussion:

“This is pretty powerful, as instead of just duplicating templates and having say 15 copies of the same template (each only slightly different) - people can build a master process and define all the little variations.”

The typical reaction is to clone. And clone again. Before you know it, you are drowning in template copies that started identical but have now diverged in ways nobody can track.

The problem compounds when you realize that rules and automations are tied to specific steps. Clone a template and suddenly your conditional logic is pointing at ghosts - steps that exist in the original but have different IDs in the copy.

The user story that defined everything

I posted a user story that became our reference point throughout development:

“User story - I ship t-shirts - and have an order fulfilment process. I ship to 8 countries, and although my process is 90% the same - it changes slightly country-by-country.”

That scenario - simple on the surface, deceptively complex underneath - captured exactly what we needed to solve. The 90% that stays constant is your core process. The 10% that varies by context should not require eight separate documents to manage.

Here is an animated concept from that early design phase showing how variation mapping would work:

Early concept animation: mapping variations across a process template. April 2018.

Early concept animation: mapping variations across a process template. April 2018.

A different approach: variations within a single template

The core idea I sketched out:

“Instead of tying it to captures or rules - we need to be able to define variations from ‘Standard’ and then visualize the difference between one variation and another.”

Rather than duplicating entire templates, you maintain one master template and mark which steps apply to which variations.

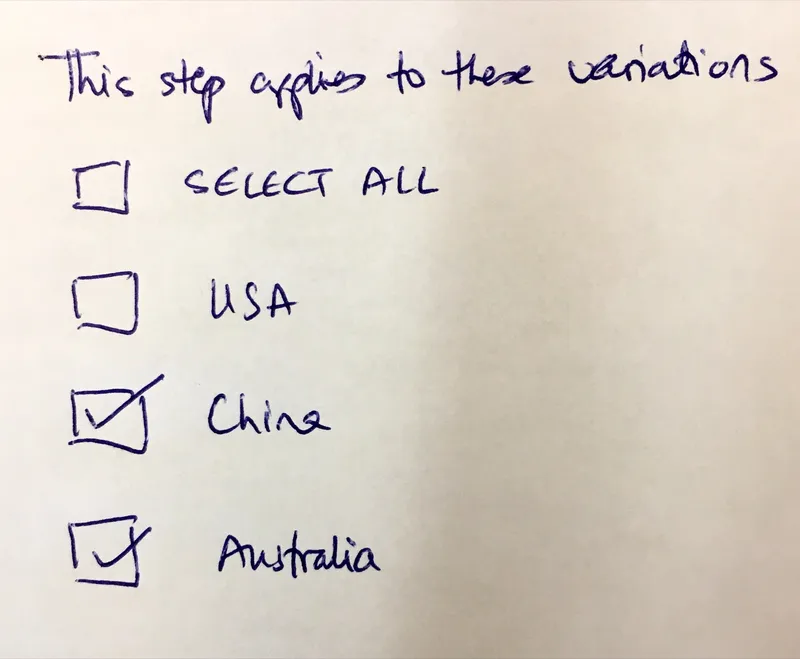

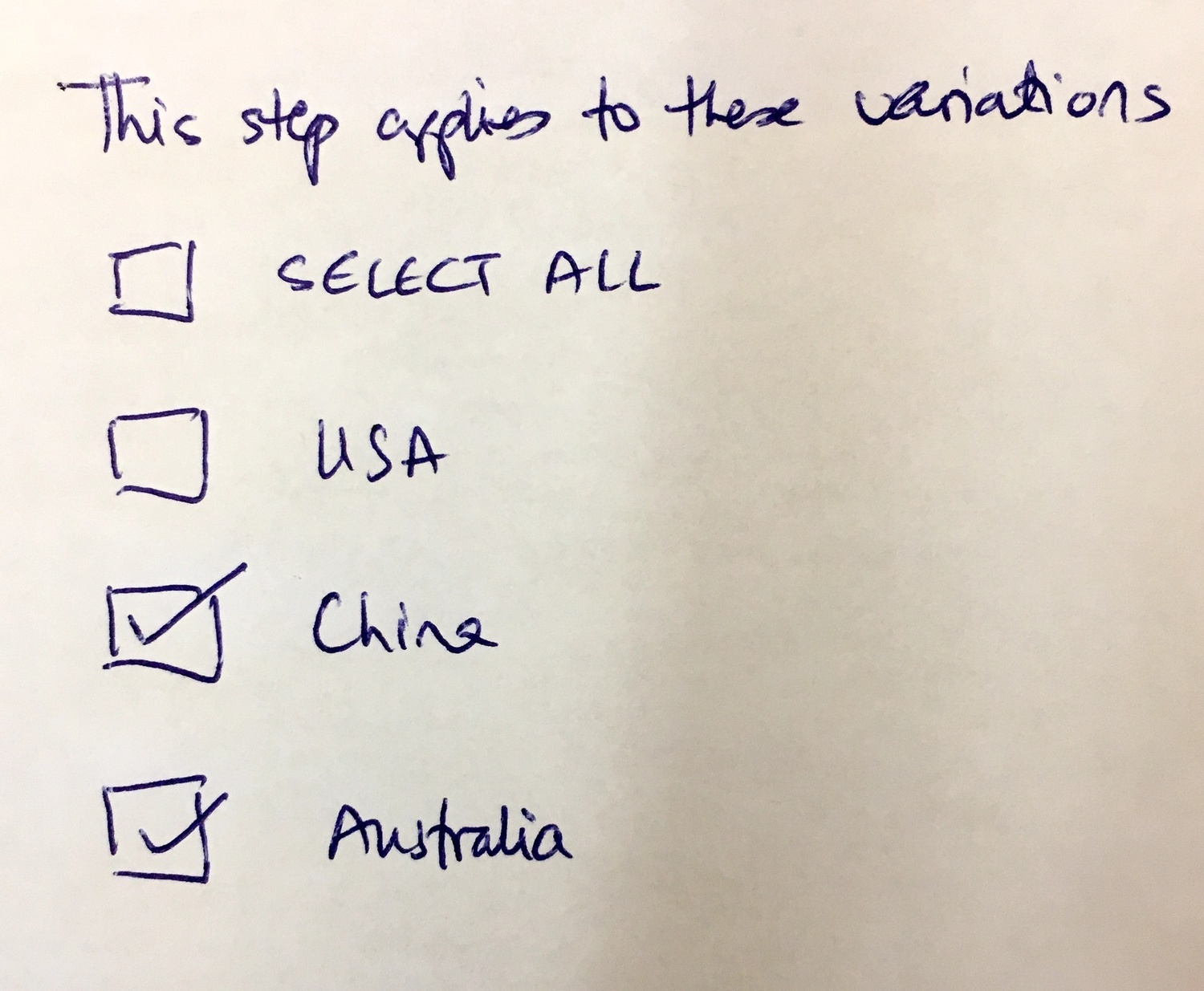

Here is the early design sketch for how a step could be tagged to specific variations:

Early design sketch: each step can be tagged to specific variations like USA, China, or Australia

The interface is simple. When you enable variations on a template, you name them - just text labels like “USA” or “China” or “Australia.”

Then when editing any step, you tick which variations it applies to.

And here is a more detailed UI sketch showing the variation selection interface:

UI concept for selecting which variations a step applies to. April 2018.

UI concept for selecting which variations a step applies to. April 2018.

Filtering the template view

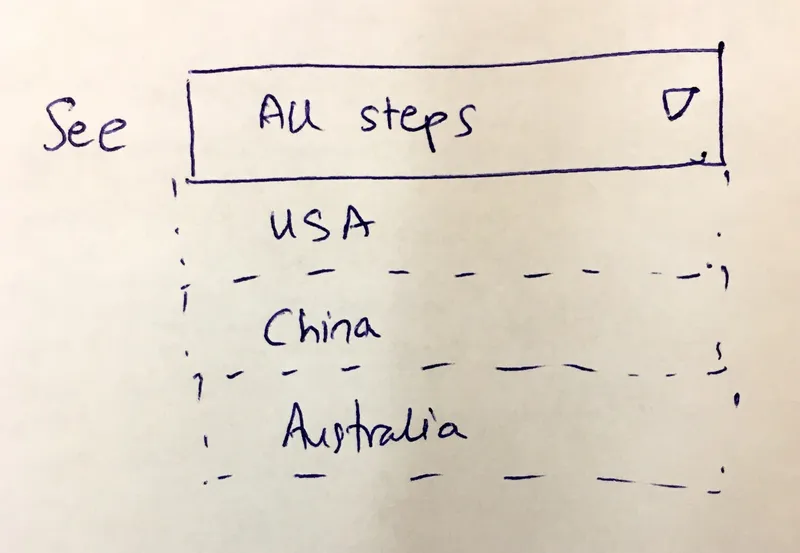

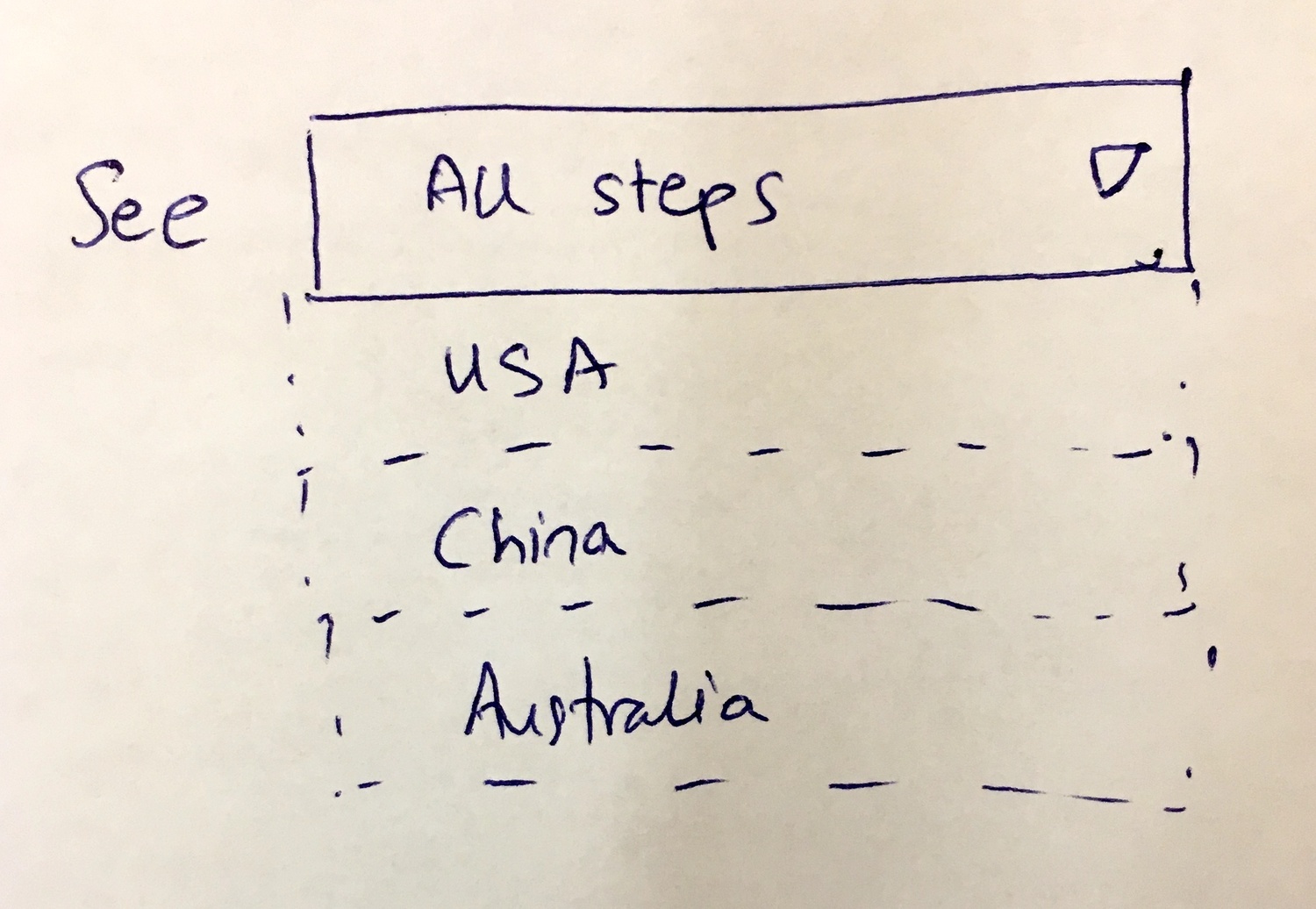

The next piece was visualization. When viewing the template editor, you can filter to see steps for a given variation:

Filter dropdown concept: view all steps or filter to see only steps for a specific variation

This is powerful because you can instantly compare what the China process looks like versus the USA process - within the same template, not across two separate documents.

Here is the more detailed dropdown design we explored:

Filter dropdown concept: quickly switch between viewing different regional variations. April 2018.

Filter dropdown concept: quickly switch between viewing different regional variations. April 2018.

Thomas, our product designer at the time, added a suggestion:

“As well there could be a subtle color change in each editor, to the grid background or step cards to indicate a different variation has been selected. Color code them basically.”

Visual differentiation makes it immediately obvious which variation context you are working in.

The tag-based alternative

We also explored using tags instead of named variations:

“Also, we could use hash tags instead of labels within steps to indicate variation groupings.”

I added:

“I believe tags for steps were already on the table elsewhere.”

This would allow more flexible groupings - a step could be tagged #china #asia #apac and appear in multiple variation contexts. But it also adds complexity. Named variations feel more bounded and easier to understand.

The rule complexity problem

Here is where it gets tricky. What happens when you have conditional logic - if-then rules - that reference steps?

“Most important impact - on IFTTT rules. Any rules would only apply within a specific, defined variation. That is a bit complex.”

And later, from internal discussion:

“The problem occurs when a rule is tied to another step which either is or is not in the current variation.”

If you have a rule that says “when Step 5 completes, assign Step 8 to the legal team” - but Step 8 only exists in the USA variation - what happens when you run the China variation?

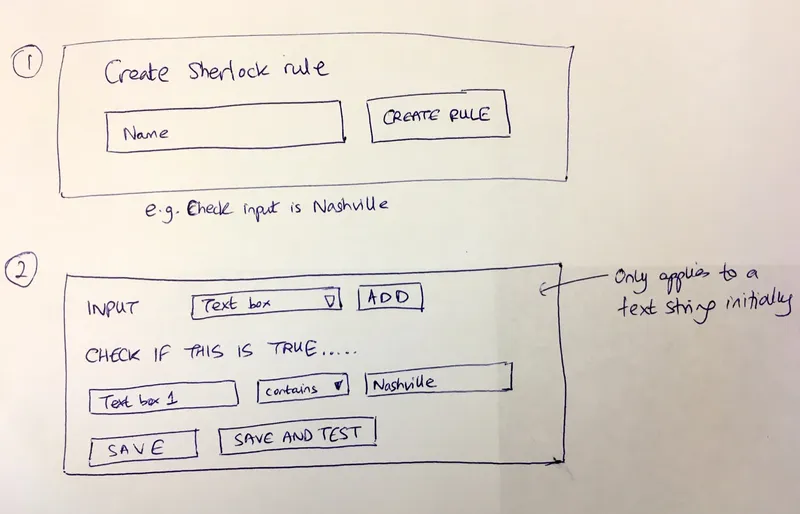

This is not a trivial problem. We sketched out conditional rule builders that could handle this complexity:

Conditional rule builder concept: create reusable rules that can be tested before deployment

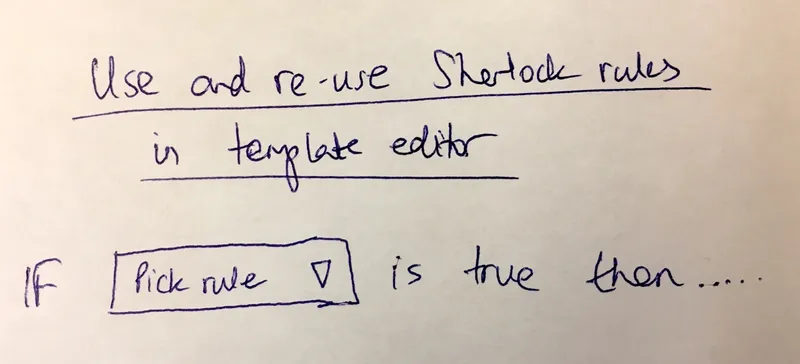

The approach we explored was making rules themselves reusable components. We called them “Sherlock rules” internally - named after the detective because they evaluate conditions and make decisions. (The full story of the Sherlock rules engine is in a separate post.)

Reusable rules concept: define a rule once and reference it across multiple templates and variations

The idea was that rules could be defined once, tested, and then referenced across variations. If a rule referenced a step that did not exist in a particular variation, the rule simply would not apply.

The recommended architecture

From our internal work on relative deadline calculation fix for dependent task completion, the engineering recommendation emerged:

“Recommended approach: keep only a single blueprint object, but internally segregate versions.”

This was the architectural decision that made variations possible without database explosions. One template. One object in the database. Multiple variations handled through internal segmentation, not duplication.

The alternative - storing each variation as a separate template with pointers to a parent - would have created the same maintenance nightmare we were trying to solve. If the China variation is a separate database object that inherits from the master, updating the master still requires propagation logic. Nightmare.

One object. Internal segregation. Clean.

Running a process with variations

When starting a process, you get an additional option - which variation do you want to run?

- None (run all steps) - default

- USA

- China

- Australia

This dropdown appears at launch time. The system then filters the template, including only the steps that apply to the selected variation, and the rules that make sense in that context.

The real customer pressure

From our work on form field data pass-through when launching linked processes, documenting why this became urgent:

“A key customer specifically will not signup until this feature is released.”

Real customer. Real deal. Waiting on variations.

This kind of pressure clarifies priorities. When a signed contract depends on a feature, you find a way to make it work. This key customer needed regional variations for their compliance workflows. Different countries, different regulatory requirements, same underlying process.

Why this matters

“Process variation management is a key strength lacking in traditional approaches like Visio, etc.”

Traditional process documentation tools treat each variation as a completely separate document. You draw one flowchart for USA, another for China, another for Australia. No connection between them. No way to see what is common versus what differs.

But in reality, your shipping process is 90% identical across all eight countries. The 10% that varies is important, but it does not justify maintaining eight separate documents.

Based on hundreds of implementations we have seen, the variation problem is most acute in consulting firms and professional services. One consulting company we worked with ran different onboarding processes depending on which client engagement a new hire was joining. The core HR steps were identical - offer letter, background check, payroll setup. But the client-specific onboarding varied dramatically: different badge requirements, different laptop setups, different security clearances. Without variations, they would have needed separate templates for every client.

One template. Multiple variations. Single source of truth for the common steps. Clear visibility into what differs.

What we left out

This design intentionally avoided several features that add complexity:

Automatic variation detection: We never built logic that would analyze multiple duplicate templates and suggest merging them into one template with variations. The mental model shift is significant enough that manual migration is better than algorithmic guessing.

Cross-variation analytics: Comparing performance metrics across variations - how does the China process compare to USA in cycle time? - requires its own reporting infrastructure. We punted on this initially.

Variation inheritance: We did not support variations inheriting from other variations. No “Asia” variation that China and Japan both inherit from. Keep it flat.

Step-level field variations: We focused on including or excluding entire steps, not on having the same step with different form fields per variation. That path leads to unmaintainable complexity.

Nested variations: We did not support variations within variations. No “China-Shenzhen” as a sub-variation of “China.” Keep it flat.

Version control per variation: All variations share the same version history. When you update the master template, you update all variations simultaneously. This is a feature, not a bug - it prevents drift.

The real insight

The deeper insight here is about documentation philosophy. At Tallyfy, we believe most workflow tools treat templates as static documents. You create one, you run it, you might clone it.

But real business processes are living things. They have a core that rarely changes and edges that vary by context. Building tools that respect this structure - that let you maintain one truth with contextual variations - changes how organizations think about their processes.

You stop asking “which template is the right one?” and start asking “what variation context am I in?”

That is a much better question.

Shipping templates that benefit from variations

These fulfillment workflows often need regional variations for customs, carriers, and compliance requirements

Related questions

How do template variations differ from conditional logic?

Conditional logic (if-then rules) evaluates at runtime based on form field values - if the customer type is Enterprise, skip the credit check step. Template variations are selected at launch time - you choose USA or China before the process starts, and that determines which steps exist at all. Both have their place. Conditional logic handles dynamic decisions within a process. Variations handle structural differences between process versions.

Can variations be combined with conditionals?

Yes, but carefully. A rule can only reference steps that exist in the current variation. If you have a rule that says “when customs clearance completes, notify legal” - and customs clearance only exists in international variations - that rule effectively becomes inactive for domestic variations. The key is designing your rules to be variation-aware, or using reusable rule components that gracefully handle missing steps.

What about reporting across variations?

This is where the single-template approach really shines. Because all variations share one template, your analytics can aggregate across all of them or filter by variation. You can answer questions like “what is the average completion time for the China variation versus USA?” without joining data from eight separate templates. The template ID stays constant - only the variation parameter differs.

How do you handle steps that are mostly similar but slightly different?

This is the hardest case. Say your pricing step has different tax calculations for each country. Two approaches work: either create separate steps (Pricing-USA, Pricing-China) each tagged to their variation, or create one pricing step that uses conditional form fields based on a country selector. We generally recommend the former for significant differences and the latter for minor tweaks like label changes.

Is this the same as process versioning?

No. Versioning handles temporal changes - the process as it was in January versus June. Variations handle contextual differences - the process for USA versus China at the same point in time. You need both. A well-designed system lets you have version 3.2 of your shipping template with USA, China, and Australia variations. Each variation can be at the same version, evolving together.

About the Author

Amit is the CEO of Tallyfy. He is a workflow expert and specializes in process automation and the next generation of business process management in the post-flowchart age. He has decades of consulting experience in task and workflow automation, continuous improvement (all the flavors) and AI-driven workflows for small and large companies. Amit did a Computer Science degree at the University of Bath and moved from the UK to St. Louis, MO in 2014. He loves watching American robins and their nesting behaviors!

Follow Amit on his website, LinkedIn, Facebook, Reddit, X (Twitter) or YouTube.

Automate your workflows with Tallyfy

Stop chasing status updates. Track and automate your processes in one place.